jax-js: an ML library for the web

JAX in pure JavaScript, as a flexible machine learning library and compiler.

I’m excited to release jax-js, a machine learning library for the web.

You can think of it as a reimplementation of Google DeepMind’s JAX framework (similar to PyTorch) in pure JavaScript.

jax-js runs completely in the browser by generating fast WebGPU and Wasm kernels.

Numerical computing on the web

Starting in February this year, I spent nights and weekends working on a new ML library for the browser. I wanted a cross-platform way to run numerical programs on the frontend web, so you can do machine learning.

Python and JavaScript are the most popular languages in the world:

JavaScript is the language of the web.

Python is simple, expressive and now ubiquitous in ML thanks to frameworks like PyTorch and JAX.

But most developers would balk at running any number crunching in JavaScript. While the JavaScript JIT is really good, it’s not optimized for tight numerical loops. JavaScript doesn’t even have a fast, native integer data type! So how can you run fast numerical code on the web?

The answer is to rely on new browser technologies — WebAssembly and WebGPU, which allow you to run programs at near-native speeds. WebAssembly is a low-level portable bytecode, and WebGPU is GPU shaders on the web.

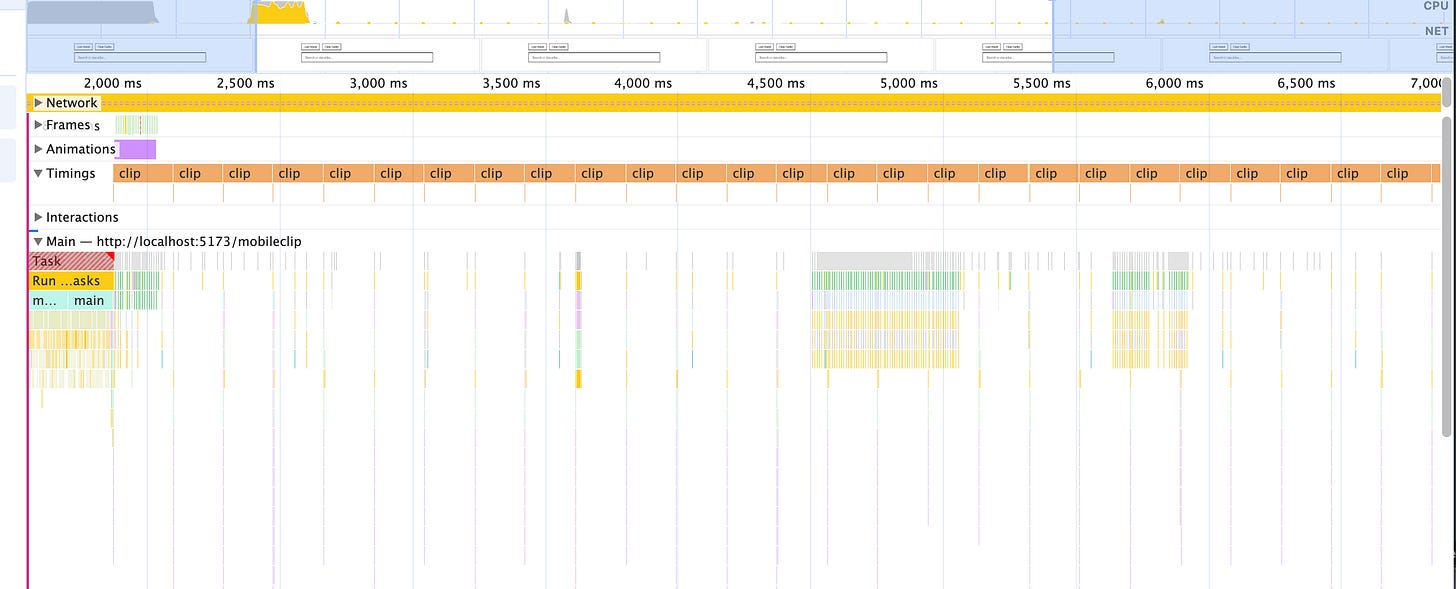

If we can use these native runtimes, then this lends itself to a programming model similar to JAX, where you trace programs and JIT compile them to GPU kernels. Here, instead of Nvidia CUDA, we write pure JavaScript to generate WebAssembly and WebGPU kernels. Then we can run them and execute instructions at near-native speed, skipping the JavaScript interpreter bottleneck.

That is what I ended up doing in jax-js, and now it “just works”.

Getting started

You can install jax-js as a library. It has 0 dependencies and is pure JS.

npm install @jax-js/jaxThen you can use it with an API almost identical to JAX.

import { numpy as np } from "@jax-js/jax";

const ar = np.array([1, 5, 6, 7]);

console.log(ar.mul(10).js()); // -> [10, 50, 60, 70]Under the hood, this generates a WebAssembly kernel and dispatches it.

Note: There are some surface-level syntax differences here, versus JAX:

JavaScript doesn’t have operator overloading like Python. Instead of

ar * 10in Python, you have to callar.mul(10).The

.js()method converts a jax.Array object back into a plain JS array.JS has no reference-counted destructor method to free memory, so array values in jax-js have move semantics like Rust, with

.refincrementing their reference counts.

If you’d like to use WebGPU, just start your program with:

import { init, setDevice } from "@jax-js/jax";

await init("webgpu");

setDevice("webgpu");You can leverage grad, vmap, and other features of JAX. Here’s automatic differentiation with grad():

import { grad, numpy as np } from “@jax-js/jax”;

const f = (x: np.Array) => np.sqrt(x.ref.mul(x).sum());

const df = grad(f);

const x = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4]);

console.log(df(x).js());And here’s an example the compiler fusing operations with jit(). The following function gets translated into a compiled GPU compute kernel:

import { jit, numpy as np } from "@jax-js/jax";

const f = jit((x: np.Array) => {

return np.sqrt(x.add(2).mul(Math.PI)).sum();

});Machine learning

With these simple building blocks, you can implement most machine learning algorithms and backpropagate through them.

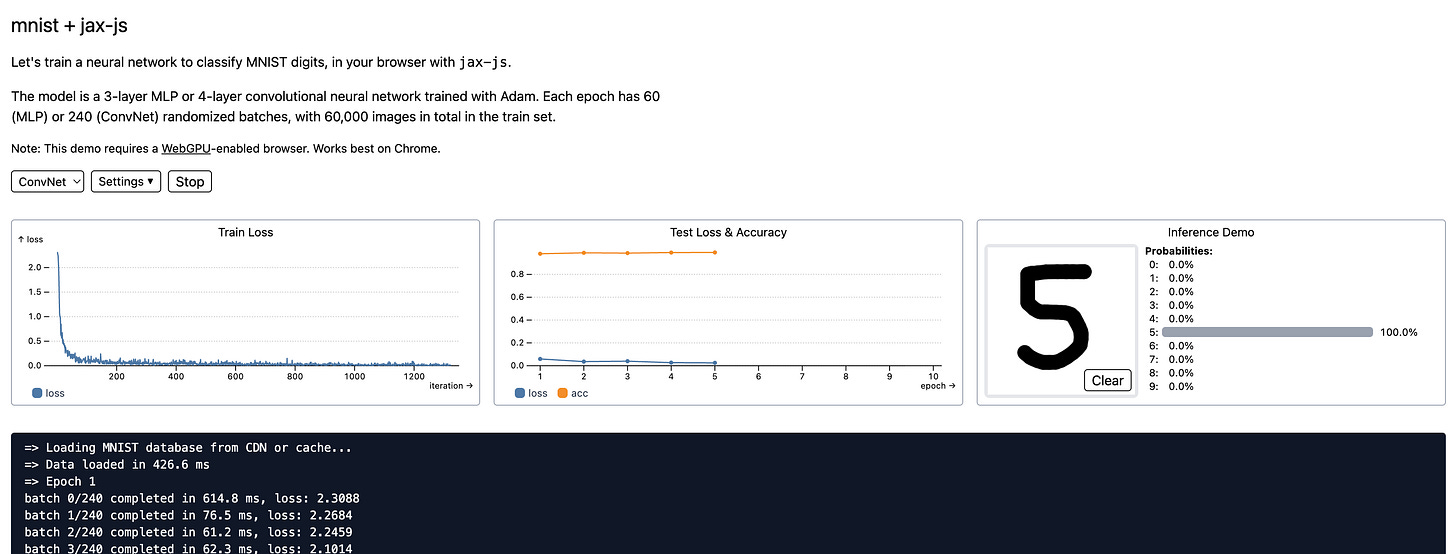

Here is a runnable example of training a neural network from scratch on MNIST dataset in your browser. It learns to >99% accuracy in seconds, and everything from dataset loading to matmul kernels is pure frontend JavaScript code.

It’s remarkable to write ML programs with hot module reloading. You can edit code in real time while the model is training!

—

You can also build applications. Here’s a demo I built yesterday: download the whole text of Great Expectations (180,000 words), run it through a CLIP-based embedding model, and semantic search it in real time—all from your browser.

(The text embedding actually runs at a respectable ~500 GFLOP/s on my M1 Pro with just jax.jit(), despite me not having tried to optimize it at all yet. Not bad, crunching 500,000,000,000 calculations/second in browser on a 4-year-old laptop!)

For a lot of inference use cases, you might find a “model runtime” like ONNX to add prebuilt ML models to your browser, where the ML developers hand off pre-packaged weights to be used in product. With jax-js, it’s a bit different, and I’m imagining how a full ML framework, usually relegated to the backend, can run in a browser.

As for performance, it hasn’t been my primary focus so far, as just “getting the ML framework working” comes first. I have checked that jax-js’s generated kernels for matmuls are fast (>3 TFLOP on Macbook M4 Pro). But there’s a lot of room to improve (e.g., conv2d is slow), and I haven’t done much optimization work on transformer inference in particular yet. There’s plenty of low-hanging fruit.

Project release

I am open-sourcing jax-js today at ekzhang/jax-js.

There are rough edges in this initial release, but it’s ready to try out now.

Links:

I look forward to seeing what you create. 🥰

Appendix

This is a personal project and not related to Thinking Machines Lab. I started working on jax-js before starting my current job, and in a way, it’s partly how I ended up working in ML. Turns out this stuff is kind of fun!

If you’re still reading, hello—I have a bunch more details to share.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to:

The authors of JAX for making an important ML library that’s a joy to use.

Thanks to Matthew Johnson, Dougal Maclaurin, and others for Autodidax, an instructive implementation of the JAX core from scratch.

And thanks for all of the JAX ecosystem libraries as well.

Tinygrad for a very excellent autograd library — you showed that code-generating kernels from scratch can’t really be that intrinsically complex!

Many parts of jax-js in the backend internals follow Tinygrad’s design closely. The biggest example of this is ShapeTracker, which was directly ported.

Chrome, Safari, and Firefox for WebGPU, now used in 2% of all websites.

The open-source community, for inspiration and for showing that ML on the web is actually possible!

How it works: An overview of internals

In general, I think there are roughly two parts to an ML library:

“Frontend” (think JAX): The interface for creating and manipulating arrays, the autograd engine, JIT, typing and transformations. Also where you interact with a sync/async boundary and how you track memory allocations.

“Backend” (think XLA): Actual kernels for executing operations. The frontend has some kind of representation of a kernel, it dispatches it to the backend, which then optimizes it, compiles it down to native code (CPU or GPU) and runs it very efficiently.

This dichotomy obviously isn’t perfect (e.g., where do Triton/Pallas fit in? how about warp-specialized cuTile?), and there are certainly concerns that span both parts. But it’s how jax-js works.

Let’s start with the backend and build our way up. In jax-js, the backend code is actually quite self-contained; they implement the Backend interface (abridged):

/** A device backend. */

export interface Backend {

/** Allocate a new slot with reference count 1. */

malloc(size: number, initialData?: Uint8Array): Slot;

/** Increment the reference count of the slot. */

incRef(slot: Slot): void;

/**

* Decrement the reference count of the slot. If the reference count reaches

* zero, it is freed. This should throw if the slot was already freed.

*/

decRef(slot: Slot): void;

/** Read a range of bytes from a buffer. */

read(

slot: Slot,

start?: number,

count?: number,

): Promise<Uint8Array<ArrayBuffer>>;

/** Prepare an expression to be executed later. */

prepare(kernel: Kernel): Promise<Executable>;

/**

* Run a backend operation that was previously prepared.

*

* The operation may not run immediately, but operations are guaranteed to run

* in the dispatch order. Also, `read()` will wait for all pending operations

* on that slot to finish.

*/

dispatch(exe: Executable, inputs: Slot[], outputs: Slot[]): void;

}In other words, backends need to be able to malloc/free chunks of memory for tensors, and to execute Kernel objects. Inside a Kernel there is:

A pointwise operation on one or more tensors, with

Lazy shape-tracking information for how to index the tensors, and

A reduction to be performed (optional).

Reductions can be any associative operation (add/multiply/max/min), and they can optionally have a fused epilogue as well.

The pointwise operation is constructed from a pure expression tree, an AluExp, where each node is a symbolic AluOp. There are 28 AluOps — you don’t need so many distinct operations when you can depend on kernel fusion!

Note that no automatic differentiation happens here; these are pure low-level operations, so we can introduce arbitrary building blocks this way.

/** Symbolic form for each mathematical operation. */

export enum AluOp {

Add = “Add”,

Sub = “Sub”,

Mul = “Mul”,

Idiv = “Idiv”,

Mod = “Mod”,

Min = “Min”,

Max = “Max”,

Sin = “Sin”,

Cos = “Cos”,

Asin = “Asin”,

Atan = “Atan”,

Exp = “Exp”,

Log = “Log”,

Erf = “Erf”,

Erfc = “Erfc”,

Sqrt = “Sqrt”,

Reciprocal = “Reciprocal”,

Cast = “Cast”,

Bitcast = “Bitcast”,

Cmplt = “Cmplt”,

Cmpne = “Cmpne”,

Where = “Where”, // Ternary operator: `cond ? a : b`

Threefry2x32 = “Threefry2x32”, // PRNG operation, arg = ‘xor’ | 0 | 1

// Const is a literal constant, while GlobalIndex takes data from an array

// buffer. Special and Variable are distinguished since the former is for

// indices like the global invocation, while the latter is a value.

Const = “Const”, // arg = value

Special = “Special”, // arg = [variable, n]

Variable = “Variable”, // arg = variable

GlobalIndex = “GlobalIndex”, // arg = [gid, len]; src = [bufidx]

GlobalView = “GlobalView”, // arg = [gid, ShapeTracker], src = [indices...]

}When auto-generating GPU kernels, they’re pretty simple for pointwise ops. The tricky part is if there’s a reduction (aka. tensor contraction), most commonly in matmuls and convolutions. These can be optimized pretty well on the web by unrolling judiciously and tiling the loads/stores.

An example WebGPU matmul kernel for float32[4096,4096] matrices generated by jax-js is shown below.

@group(0) @binding(0) var<storage, read> in0 : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(1) var<storage, read> in1 : array<f32>;

@group(0) @binding(2) var<storage, read_write> result : array<f32>;

@compute @workgroup_size(256)

fn main(@builtin(global_invocation_id) id : vec3<u32>) {

if (id.x >= 1048576) { return; }

let gidx: i32 = i32(id.x);

var acc0: f32 = f32(0);

var acc1: f32 = f32(0);

var acc2: f32 = f32(0);

var acc3: f32 = f32(0);

var acc4: f32 = f32(0);

var acc5: f32 = f32(0);

var acc6: f32 = f32(0);

var acc7: f32 = f32(0);

var acc8: f32 = f32(0);

var acc9: f32 = f32(0);

var acc10: f32 = f32(0);

var acc11: f32 = f32(0);

var acc12: f32 = f32(0);

var acc13: f32 = f32(0);

var acc14: f32 = f32(0);

var acc15: f32 = f32(0);

for (var ridx: i32 = 0; ridx < 1024; ridx++) {

let x0: i32 = ((gidx / 8192) * 131072) + ((((gidx / 8) % 8) * 16384) + (ridx * 4));

let x1: f32 = in0[x0];

let x2: i32 = (((gidx / 64) % 128) * 32) + (((gidx % 8) * 4) + (ridx * 16384));

let x3: f32 = in1[x2];

let x4: f32 = in0[x0 + 1];

let x6: f32 = in0[x0 + 2];

let x8: f32 = in0[x0 + 3];

let x10: f32 = in0[x0 + 4096];

let x11: f32 = in0[x0 + 4097];

let x12: f32 = in0[x0 + 4098];

let x13: f32 = in0[x0 + 4099];

let x14: f32 = in0[x0 + 8192];

let x15: f32 = in0[x0 + 8193];

let x16: f32 = in0[x0 + 8194];

let x17: f32 = in0[x0 + 8195];

let x18: f32 = in0[x0 + 12288];

let x19: f32 = in0[x0 + 12289];

let x20: f32 = in0[x0 + 12290];

let x21: f32 = in0[x0 + 12291];

let x22: f32 = in1[x2 + 1];

let x26: f32 = in1[x2 + 2];

let x30: f32 = in1[x2 + 3];

let x5: f32 = in1[x2 + 4096];

let x23: f32 = in1[x2 + 4097];

let x27: f32 = in1[x2 + 4098];

let x31: f32 = in1[x2 + 4099];

let x7: f32 = in1[x2 + 8192];

let x24: f32 = in1[x2 + 8193];

let x28: f32 = in1[x2 + 8194];

let x32: f32 = in1[x2 + 8195];

let x9: f32 = in1[x2 + 12288];

let x25: f32 = in1[x2 + 12289];

let x29: f32 = in1[x2 + 12290];

let x33: f32 = in1[x2 + 12291];

acc0 += x1 * x3 + x4 * x5 + x6 * x7 + x8 * x9;

acc1 += x10 * x3 + x11 * x5 + x12 * x7 + x13 * x9;

acc2 += x14 * x3 + x15 * x5 + x16 * x7 + x17 * x9;

acc3 += x18 * x3 + x19 * x5 + x20 * x7 + x21 * x9;

acc4 += x1 * x22 + x4 * x23 + x6 * x24 + x8 * x25;

acc5 += x10 * x22 + x11 * x23 + x12 * x24 + x13 * x25;

acc6 += x14 * x22 + x15 * x23 + x16 * x24 + x17 * x25;

acc7 += x18 * x22 + x19 * x23 + x20 * x24 + x21 * x25;

acc8 += x1 * x26 + x4 * x27 + x6 * x28 + x8 * x29;

acc9 += x10 * x26 + x11 * x27 + x12 * x28 + x13 * x29;

acc10 += x14 * x26 + x15 * x27 + x16 * x28 + x17 * x29;

acc11 += x18 * x26 + x19 * x27 + x20 * x28 + x21 * x29;

acc12 += x1 * x30 + x4 * x31 + x6 * x32 + x8 * x33;

acc13 += x10 * x30 + x11 * x31 + x12 * x32 + x13 * x33;

acc14 += x14 * x30 + x15 * x31 + x16 * x32 + x17 * x33;

acc15 += x18 * x30 + x19 * x31 + x20 * x32 + x21 * x33;

}

let x34: i32 = ((gidx / 8192) * 131072) + ((((gidx / 64) % 128) * 32) + ((((gidx / 8) % 8) * 16384) + ((gidx % 8) * 4)));

result[x34] = acc0;

result[x34 + 4096] = acc1;

result[x34 + 8192] = acc2;

result[x34 + 12288] = acc3;

result[x34 + 1] = acc4;

result[x34 + 4097] = acc5;

result[x34 + 8193] = acc6;

result[x34 + 12289] = acc7;

result[x34 + 2] = acc8;

result[x34 + 4098] = acc9;

result[x34 + 8194] = acc10;

result[x34 + 12290] = acc11;

result[x34 + 3] = acc12;

result[x34 + 4099] = acc13;

result[x34 + 8195] = acc14;

result[x34 + 12291] = acc15;

}If you’re writing a native library, this isn’t good enough. For example, you have to at least use tensor cores mma.sync.aligned.* on Nvidia GPUs! But on the web, it gets to pretty comparable performance with the best open-source libraries, and it seems that Dawn is alright at bridging any gaps with optimization.

Onto the frontend. This is the core of the library, and where the actual autograd and tracing happens. We follow the JAX design quite closely, where there is a set of primitives along with an ambient interpreter stack. This is… quite difficult, magical, and took me a while to figure out. To learn more see:

The simple essence of automatic differentiation (Elliott 2018)

(One particularly cool moment about this way of building an ML library is that you get reverse-mode AD “for free” by inverting/transposing the forward-mode rules. I found this really beautiful after I wrapped my head around it; it’s quite mathematically pleasing. Another cool moment is when you first get arbitrary 2nd, 3rd, … n-th order derivatives after just implementing the first-order derivative rules — GradientTape could never!)

Honestly this is probably the most lost I’ve ever felt in writing code. It’s like, nested mutually recursive interpreters to model functors in the “category of tensors.”

Anyway, once I reviewed my differential geometry notes from college and dusted off my understanding of tangents, pulling back cotangents, functors and so on, I think I eventually figured it out. Though I still had tiny bugs for the next 6 months. 😂

The list of high-level Primitive in jax-js is below:

/**

* Frontend primitive operations, which are lowered into Kernel objects before

* being dispatched to the backend.

*

* Any operation between arrays can be described in these parts. This is also

* the set of primitives that can occur in Jaxpr programs, and the level at

* which transformations like vmap, grad, and jvp occur. They are loosely based

* on [XLA](https://openxla.org/xla/operation_semantics).

*

* All n-ary operations support broadcasting, with NumPy semantics.

*/

export enum Primitive {

Add = “add”,

Mul = “mul”,

Idiv = “idiv”,

Neg = “neg”,

Reciprocal = “reciprocal”,

StopGradient = “stop_gradient”,

Cast = “cast”,

Bitcast = “bitcast”,

RandomBits = “random_bits”,

Sin = “sin”,

Cos = “cos”,

Asin = “asin”,

Atan = “atan”,

Exp = “exp”,

Log = “log”,

Erf = “erf”,

Erfc = “erfc”,

Sqrt = “sqrt”,

Min = “min”,

Max = “max”,

Reduce = “reduce”,

Dot = “dot”, // sum(x*y, axis=-1)

Conv = “conv”, // see lax.conv_general_dilated

Pool = “pool”,

PoolTranspose = “pool_transpose”,

Compare = “compare”,

Where = “where”,

Transpose = “transpose”,

Broadcast = “broadcast”,

Reshape = “reshape”,

Flip = “flip”,

Shrink = “shrink”,

Pad = “pad”,

Gather = “gather”,

JitCall = “jit_call”,

}Notice that many of these are similar to the backend operations above, but some are different. In particular, there are convolutions and matrix multiplications here. These are useful to see in the frontend IR (and for autograd) but can be lowered to a simpler form before the kernels are generated on the backend.

By default, an operation is just lowered directly to a backend kernel after passing through any necessary transformations (vmap, jvp, grad). But if you’re using the jit, jax-js will trace your program to produce a “Jaxpr” (list of operations) followed by automatic kernel fusion to generate kernels, specialized to each input shape.

Bugs

It’s very hard to build an ML framework and a long task! So far, jax-js has implemented a lot of core functionality in JAX, but there’s still much more. If there’s an API or operation you want to see, please consider adding it or filing an issue (examples: np.split, FFT, AdamW).

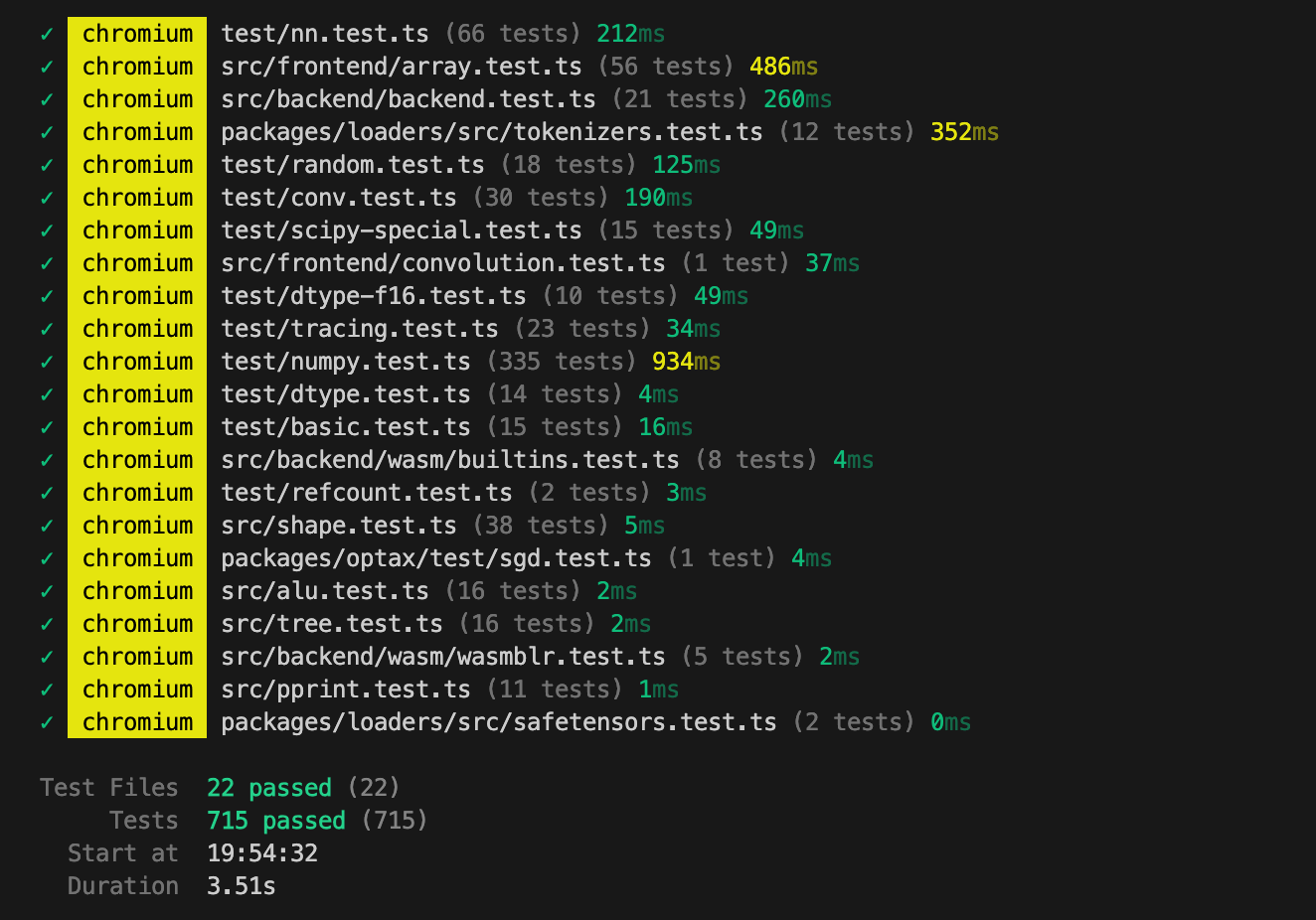

I have a pretty varied, portable test suite that runs fast:

So we are in a good position to find bugs and fix them. But making an ML library is quite difficult, and WebGPU is a nascent technology (e.g., I somehow gave my MacBook kernel panics)—there will be bugs! Please report.

Technical: Performance

We haven’t spent a ton of time optimizing yet, but performance is generally pretty good. jit is very helpful for fusing operations together, and it’s a feature only available on the web in jax-js. The default kernel-tuning heuristics get about 3000 GFLOP/s for matrix multiplication on an M4 Pro chip (try it).

On that specific benchmark, it’s actually more GFLOP/s than both TensorFlow.js and ONNX, which both use handwritten libraries of custom kernels (versus jax-js, which generates kernels with an ML compiler).

Some particularly useful / low-hanging fruit to look at:

The WebAssembly backend currently is quite simple, I didn’t spend a ton of time optimizing it, but measurably it could be >150x faster on my MacBook Pro. This difference comes from a few things multiplying:

Don’t recompute loop indices each time, we could improve FLOPs by ~1-3x.

Do loop unrolling/tiling, will improve FLOPs by ~2-3x.

Use SIMD instructions. This would improve FLOPs by 4x.

Add multi-threading (10x on my laptop), to use all available cores. Requires SharedArrayBuffer (crossOriginIsolated) / there are some caveats here to sync/async handling, needs to be done carefully.

Running the forward pass of the MobileCLIP2 transformer model is only about 1/3 the FLOPs compared to pure 4096x4096 matmul. Maybe we can improve this, especially in the causal self-attention layer.

Although WebGPU is rapidly gaining in popularity and support, it’s probably worth having a WebGL backend as well, as a fallback that’s guaranteed to work in pretty much all browsers and is still pretty fast. This isn’t a huge amount of work; the WebGPU backend is <700 lines of code for example.

Technical: Feature parity

jax-js strives for approximate API compatibility with the JAX python library (and through that, NumPy). But some features vary for a few reasons:

Data model: jax-js has ownership of arrays using the

.refsystem, which obviates the need for APIs likejit()‘sdonate_argnumsandnumpy.asarray().Language primitives: JavaScript has no named arguments, so method call signatures may take objects instead of Python’s keyword arguments. Also, PyTrees are translated in spirit to “JsTree” in jax-js, but their specification is different.

Maturity: JAX has various types like

complex64, advanced functions likehessenberg(), and advanced higher-order features likelax.while_loop()that we haven’t implemented. Some of these are not easy to implement on GPU.

Other features just aren’t implemented yet. But those can probably be added easily!

I’ve made a table of every JAX library feature and its implementation status in jax-js, see here. There are a couple big ones that stand out.

You’re welcome to contribute, though I’d also love if you could try using jax-js. :D

The hot module reloading angle is underrated here. Beign able to tweak hyperparameters or model architecture mid-training without restarting the entire process changes the dev loop completely. I've wasted so much time in jupyter notebooks rerunning cells because I forgot to adjust a learning rate schedule. The WebGPU kernel generation approach is smart too, generating kernels on the fly gives more flexibility than shipping prebuilt binaries like ONNX runtime. Curious how the move semantics play out in practice tho, coming from Python's GC model to explicit ref counting seems like it could trip people up initially.

This is huge